How to Control and Treat Fusarium Wilt, Blight, and Rot

Finding diseases in the garden is never fun, and Fusarium is a common one. Fusarium wilt, blight, and rot causes serious damage to a wide range of plants. Horticultural expert Lorin Nielsen explains how to tackle this garden disease.

Contents

Anyone who’s been gardening for a while is familiar with the dreaded Fusarium wilt. Also called damping off, this fungal disease causes newly-sprouted seedling stems to collapse. It’s frustrating, but it’s certainly not unknown.

But did you know that Fusarium itself is a widespread genus of multiple species of soil-borne pathogens, which can also cause a number of blights and rots? In fact, Fusarium species create a number of dangers not just for your plants, but even for you.

Let’s go over what Fusarium is and learn about how and what it does. Then, we’ll go into ways to prevent it and information on how to fight back!

Overview

|

Scientific Name(s)

Fusarium oxysporum, Fusarium culmorum, Fusarium solani, etc.

Family

Nectriaceae

Origin

Worldwide

|

Plants Affected

Extremely wide range of plants, including trees, grasses, ornamentals and food crops.

Common Remedies

Fungal elimination through superheating soil or soil solarizing. Mycorrhizal and bacterial treatments somewhat effective. Prevention through sterile pruning practices, crop rotation, moisture regulation, planting resistant varieties, and proper air circulation.

|

What Is Fusarium?

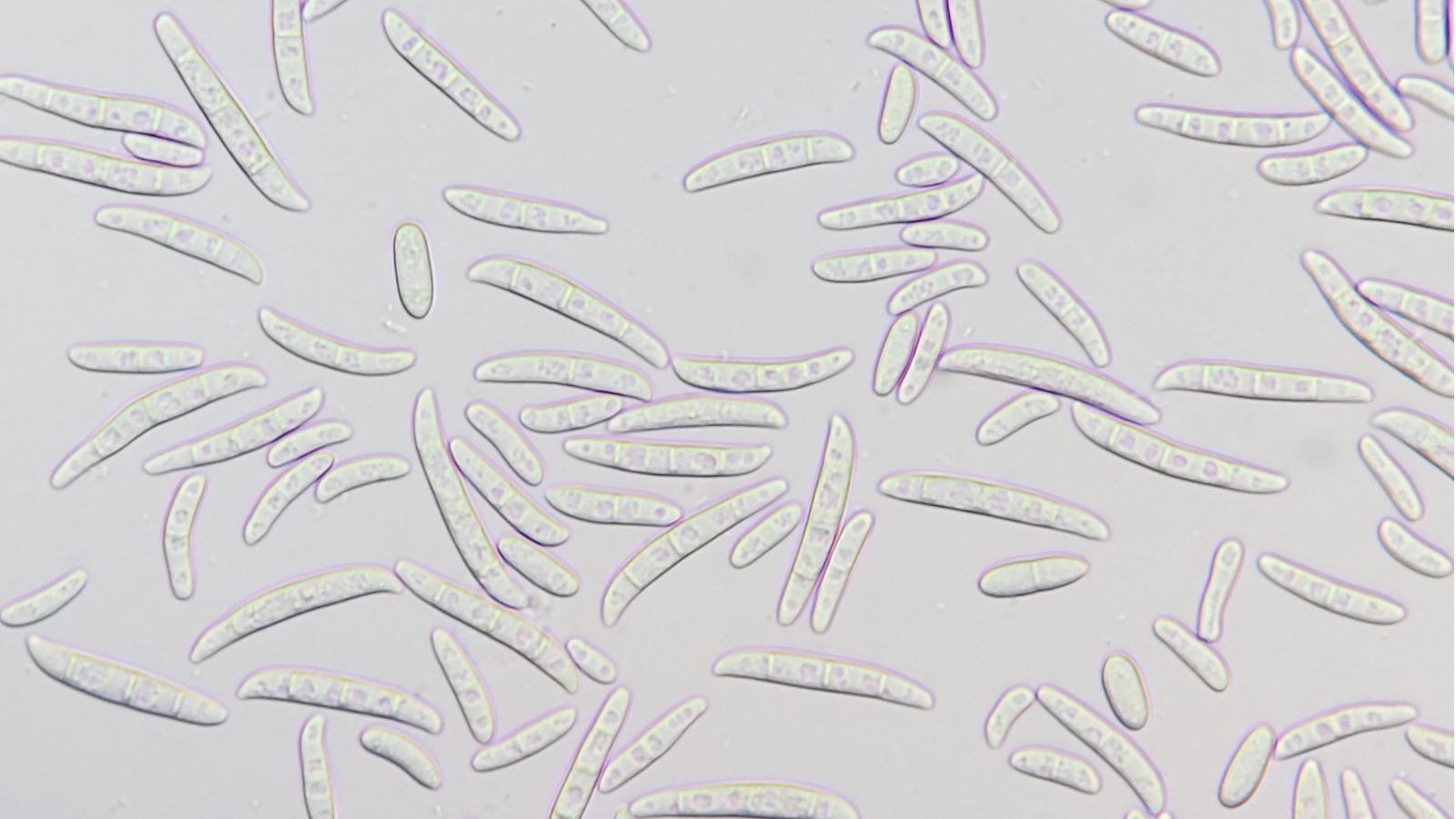

The Fusarium genus is a large group of fungal hyphomycetes. Sometimes considered anamorphic, these are often considered to be a form of mold.

However, like many fungi, it has mycelium that can spread throughout soil and, in some cases, throughout plant vascular tissue. While it is impossible to see the mycelium without the aid of a microscope, that doesn’t mean they don’t exist!

Similarly, spores can linger in soil or on plant matter. Fusarium consumes both living and dead plant material, which means it’s important to keep garden beds free of debris.

Types Of Fusarium

Fourteen different species of Fusarium cause varying damage to our crops and plants. However, amongst those fourteen species are hundreds of strains, each one specialized to infect a different type of plant.

Some of the most common forms of Fusarium infection in plants are listed below. This isn’t a complete list, but these are the ones most prevalent in home gardens or agricultural settings.

Fusarium oxysporium

With over 120 different strains, Fusarium oxysporium is the most common cause of damping off, also known as Fusarium wilt disease.

The Fusarium wilt of tomato is caused by Fusarium oxysporium sp. lycopersici. While that strain may exist in the soil, it will only impact tomatoes. Other plants are immune to that strain, but not to all other Fusarium oxysporium.

Fusarium oxysporium can also cause basal rot in a number of plants. This rot will destroy the root system. In addition, fruiting plants can have fruit rot caused by this strain.

A few strains of Fusarium oxysporium are also dangerous to humans. While these strains typically impact people with weakened immune systems, they can cause dangerous infections.

Fusarium culmorum

This Fusarium species is particularly dangerous in agriculture. Among the diseases it causes are seedling blight, fusarium head blight, root rot, and foot rot.

Considered especially dangerous amongst wheat, maize, barley, oat, and rye, it’s not limited to those plants alone. It can also impact carrots, asparagus, potatoes, and others with rot issues. This particular Fusarium species can infect lawn grasses as well, especially Kentucky bluegrass and fescue species.

If not prevented, the buildup of Fusarium culmorum that causes head blight can also produce mycotoxins that are harmful to humans or animals.

Fusarium solani

This plant pathogen causes soft rots in the roots of its host plants. It is also dangerous to humans, as it can cause a number of infections or eye conditions. The fungus can also cause problems for some species of turtle.

Plants that are hosts to Fusarium solani include citrus and avocado trees, passion fruit, peas, orchids, squash, potatoes, peppers, and groundnuts like peanuts.

Fusarium sporotrichioides

Another major cause of Fusarium head blight, Fusarium sporotrichioides primarily impacts cereal and grain crops. The infected heads can cause health risks to humans who eat the damaged grain.

While not as damaging to agriculture as some other Fusarium species, this particular species does tend to appear in conjunction with other Fusarium types, and can be a warning sign of major problems to come.

Fusarium verticillioides

This species is the most common one reported to damage maize crops. It can change the genetic pattern in the crops, causing cob and stalk rot among other issues. It can also affect wheat, sugarcane, sorghum, coconut palm, sunflower, asparagus, banana, and rice.

While it is less prevalent on other forms of crop, this Fusarium species can be damaging to livestock. As corn is a common part of livestock feed, the toxins it creates are a high risk.

Fusarium graminearum

Prevalent in wheat and barley, Fusarium graminearum causes shriveling of wheat kernels in the seed head. However, it changes the amino acids of the grain as well, resulting in major risks to livestock and humans.

Vomiting, reproductive defects, and liver damage have been reported in livestock that have eaten grain carrying the mycotoxin this species generates. Humans can also be harmed by consumption.

It’s estimated that the damage done to agriculture by this particular Fusarium species is in the billions of dollars each year, and as of yet, there are no resistant varieties.

Symptoms of Fusarium Wilt

There are three major categories of damage that Fusarium species inflict. Symptoms can vary widely, so let’s dive into it!

Wilt Disease

The first form of Fusarium wilt most people will encounter is in seedlings. This infection causes newly-sprouted seedlings to essentially collapse from a type of stem rot. To the inexperienced eye, it may seem like damage from cutworms or other pests, but it’s usually an effect of contaminated soil.

If plants survive past those initial stages but are still infected, the fusarium wilt starts restricting water flow through the plant’s stems and leaves. This causes yellowing, curling of leaves, and wilting of infected branches.

Damage appears from the lowest portion of the plant and travels upward as the fungus spreads. Lower leaves and branches will show the first signs, and it sometimes only appears on one side of the plant.

Fusarium Blight

Fusarium blight happens often in turf grasses such as Kentucky bluegrass or tall fescue. Beginning as a circular greyish-green area, it rapidly turns reddish-brown and then yellows out. The grass in each spot dies out quickly.

Fusarium head blight, on the other hand, is a common problem amongst grain crops. The seed head will show sudden signs of color change, turning from green to yellow in a patchy fashion. Leaves of infected stems may also yellow.

Fusarium Rot

Cucurbits are especially at risk from Fusarium fruit rots, including most pumpkins, watermelons, zucchini, and the like. If you’ve ever seen a pumpkin that has what appears to be scars on its side, that likely was caused by Fusarium.

In cantaloupe and other softer-rind melons, the fungus can cause the exterior of the melon to rot and collapse inward on itself. Harder-rind produce, such as pumpkin or watermelon, can tolerate some limited damage while still remaining edible, but the exterior will be marred by the fungus.

Fusarium root rot can strike a number of different plants as well. This, and other rots, are more likely to occur if the plant itself is stressed or damaged in some way.

Root-knot nematodes and cucumber beetles can spread root rot, along with other pests. As the plant is already under attack from the pest, the fungus has an immediate point of entry and will move in to colonize the root system.

These root rots are a danger when soils are too moist, as well as when plants are stressed by a lack of water during the hotter times of year. These rots cause stunted growth, yellowing or chlorosis of leaves, and can lead to plant death.

Finally, there are Fusarium stem and Fusarium crown rot, both of which typically begin with a root rot issue. The crown rots usually impact bulb plants like tulips, where the stem disease is generally a root rot that has spread. Both of these cause significant yellowing of leaves and wilting of the plant.

How To Prevent Fusarium Diseases

Prevention is the best protection against Fusarium wilt and other diseases. Let’s talk about planting resistant varieties and treating the plant disease in other ways.

Tool Sterilization

Sterilize your tools regularly. I keep a small bucket with a solution of one part bleach to nine parts water beside me, and I regularly dip my pruning shears between cuts. Be sure to completely sterilize the blade when you’re moving between plants.

As Fusarium is in the soil, you need to do the same with shovels, weeding tools, and pretty much every other garden tool. Anything that can make contact with the plant or the soil is at risk of becoming a carrier for fungal spores.

Prune Damaged Foliage

Removing infected plants is important from the minute you identify them. Sterilize your shears between every cut, remove damaged foliage, and dispose of it. Do not compost this plant material!

The same is true of infected seed heads from Fusarium blight, along with fruits or vegetables showing external signs of Fusarium-based rots. Dispose of these entirely, and don’t risk further contamination in your yard.

Severely damaged plants should be removed and disposed of to try to keep the infection at bay. If you have infected transplants, it’s vital to throw them away (even if it hurts to do).

Plant Resistant Varieties

By choosing plants with resistance to Fusarium wilt, you’ll have a much easier time controlling it. Even if those resistant cultivars do start to suffer, they do much better against the plant disease than non-resistant cultivars.

Crop Rotation

Once a bed has been contaminated by fungal spores of Fusarium wilt, you have infected soil, and any future plants that are at risk for Fusarium will have problems there. It’s essential to practice good crop rotation to protect against this issue.

Crop rotation has other benefits as well. As an example, if you plant tomatoes in the same place year after year, the soil will become depleted of the nutrients that tomatoes crave. Switching the crop ensures the soil has time to recover from each type of plant.

Fusarium wilt, rot, and blight-producing fungi can live in the soil for up to four years. Since they typically only affect a given type of crop, you can usually identify the crops at risk and avoid planting them in the same spot.

Avoid Soggy Soil

Most plants prefer well-draining soil. With the exception of plants like water chestnuts that thrive in a puddle, most don’t want to have soggy roots.

Using soil that drains excess water away quickly is important for preventing Fusarium wilt. Wilt disease develops rapidly in overly wet environments. Soggy soil or mud is the perfect place for a Fusarium outbreak to strike, as a splash can send it up onto the leaves.

Avoid watering if your soil is still damp. If you’re worried about your plants being underwatered, don’t be. Unless you forget about your plants entirely in the middle of the summer, they’re probably going to be okay if you skip a day or two of watering to let the soil dry out a bit.

But Don’t Let It Get Too Dry

Where moisture can be a risk factor for Fusarium wilt, so can extremely dry soil. If your soil is sandy or just doesn’t retain any moisture at all, it can be a perfect storage habitat for fungal spores. And heat-stressed plants are more at risk for Fusarium infection.

Ideal conditions will vary, and it can be tricky to maintain the perfect water level. If your soil seems damp to the touch but not soggy and not dry, you’ve probably got it right. Be more attentive during hot periods to make sure your plants have the right level of moisture.

Sow Seeds The Right Way

It seems appealing to sow seeds heavily. After all, you’ll be sure something will germinate, and you can always thin them out later, right?

But this creates an environment where evaporation around the seeds can be slowed. Some seeds release a gel to stay hydrated, and those gels can form a blob. Since Fusarium wilt thrives in wetter environments, that can be a problem.

Rather than sowing a bunch in a single hole, try to space them out. One to three seeds in a hole may be fine, but more than that may cause problems.

It’s also important to avoid planting seeds too deeply. If a seed only needs a light covering of soil to germinate, planting it deeper only slows seedling emergence. The longer the sprout is underground, the higher the Fusarium wilt risk.

Promote Airflow

Good air circulation around your plants helps prevent all sorts of plant diseases. While it notably protects against powdery mildew and downy mildew, it can also help your plants fight off wilts, rots, and blights.

Keep bushier plants pruned to allow for good air circulation around the plant’s main stem. Keep an eye on the seed heads of grain plants to ensure they have access to light and air, too.

Don’t forget that your soil also needs to be able to breathe, or your plant’s roots won’t have the air they need. This is yet another reason why good drainage is essential!

Fusarium Control Methods

While there are no simple sprays available right now that clear up fusarium-based fungal growth, that doesn’t mean that there aren’t possible methods to control it! It’s just a lot trickier to achieve.

Heat Treating Soil

A promising treatment method for Fusarium wilt is heating soil temperatures to above 140°F (60°C). This can be done through soil solarization. Smaller quantities of soil can also be placed in the oven to kill off any weed seeds or fungal growth.

However, increasing soil temperatures requires some time and can take quite a bit of work. If you’re solarizing the soil, this can take a couple of months or longer, plus you need to completely clear the area before you begin.

For oven treatment, it depends on the temperature you’re cooking the soil at, but it’ll still take at least an hour at 140-150°F (60-66°C), or half an hour at 180-200°F (82-93°C). Then, of course, it must go into a clean container or bed that is free of the pathogens you just killed.

Both forms of heat treatment will kill off many beneficial soil bacteria and mycorrhizae. It also kills off worms and other beneficial soil-dwellers. You will need to re-add your beneficial nematodes, bacteria, and mycorrhizae to the soil after you raise soil temperatures beyond their tolerance.

Mycorrhizal and Bacterial Treatment

Research is still being done about the benefits of various mycorrhizae against the fungal growth of Fusarium wilt and how it all works. Science has not established everything as of yet. But we do know some things, at least.

Trichoderma viride, Trichoderma harzianum, and Trichoderma virens have all been tested against Fusarium, and all three have been shown to have some effect on reducing Fusarium in the soil.

In an interesting study focusing on Trichoderma and how they affect Fusarium oxysporium in chickpeas, a combination of Trichoderma harzanium and a seed-coating fungicide called carboxin was the most effective at reducing Fusarium wilt.

This combination proved to have a 44-60% likelihood of reducing the frequency of Fusarium wilt. Added benefits included a boost in seed germination rates, as well as better overall yields per plant at harvest time.

Streptomyces fungi are also being incorporated into soil to good effect. Streptomyces griseoviridis is showing enough promise against Fusarium that it’s being sold now as a biofungicide.

Bacterial treatment is also proving to be beneficial, especially with Bacillus subtilis and Bacillus amyloliquefaciens.

Bacillus subtilis is a common seed inoculant, both to protect against plant disease and to help improve the breakdown of insoluble phosphorus in the soil. Bacillus amyloliquefaciens is used in hydroponics, agriculture, and aquaponics to help clear up the effects of Fusarium.

Incorporating these into your soil is an effective treatment strategy to reduce or remove the effects of Fusarium-based diseases.